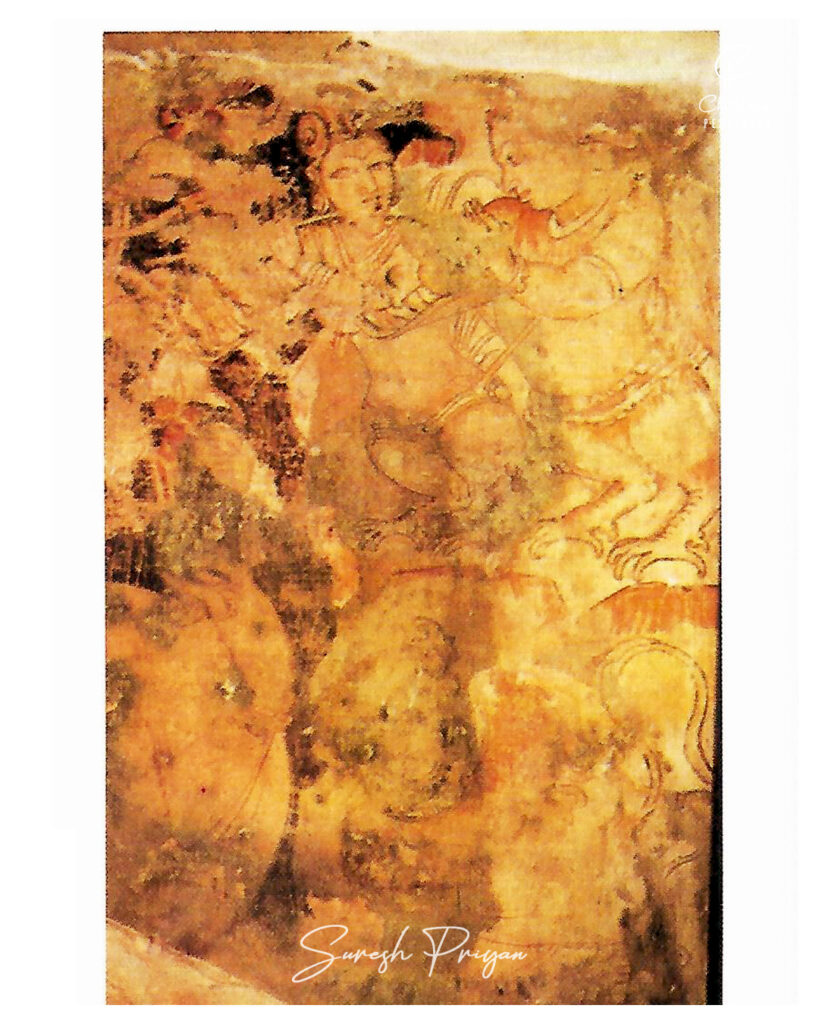

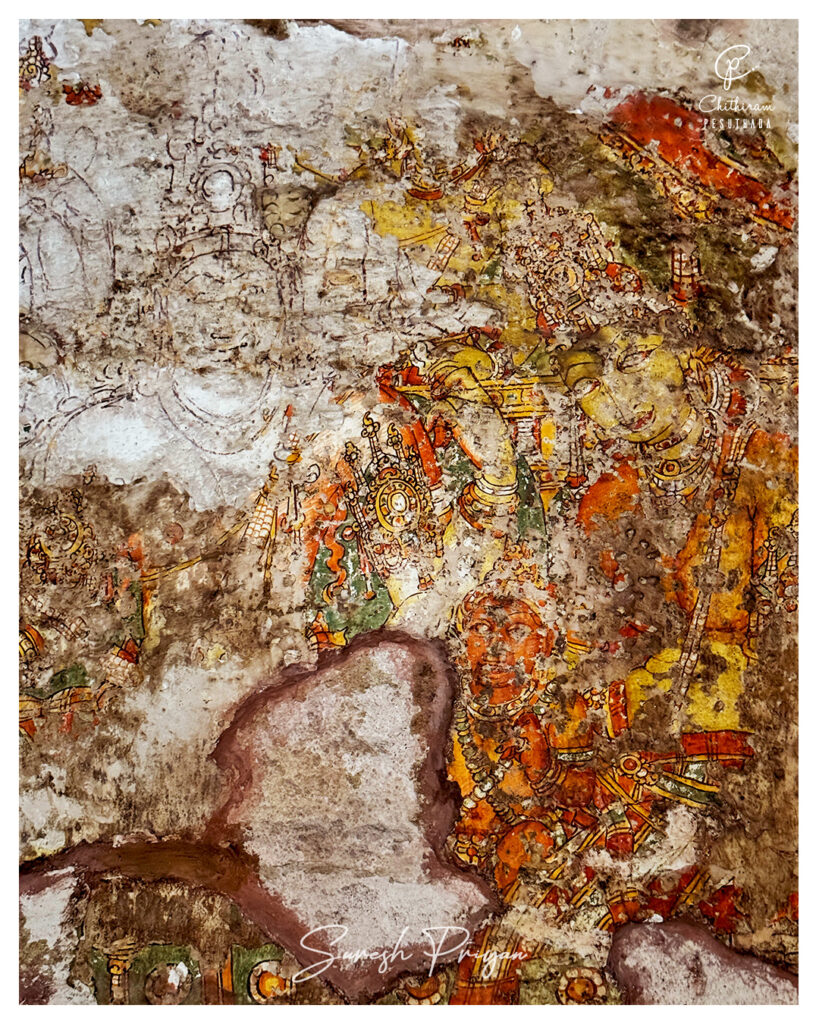

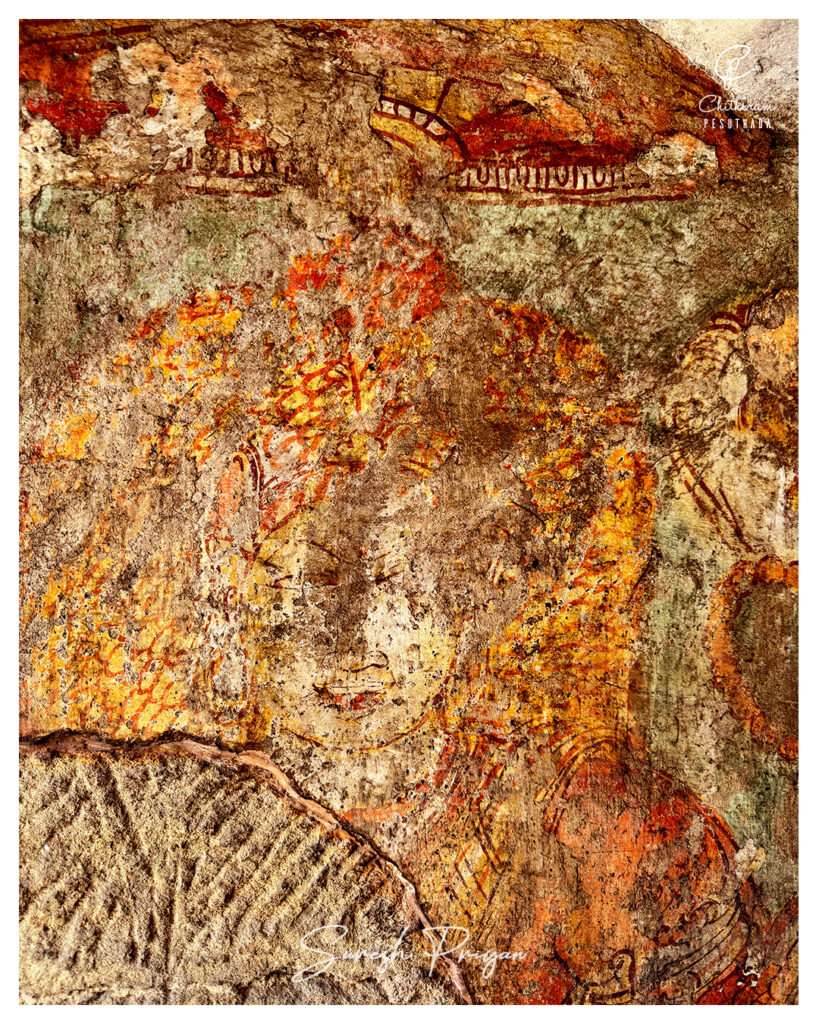

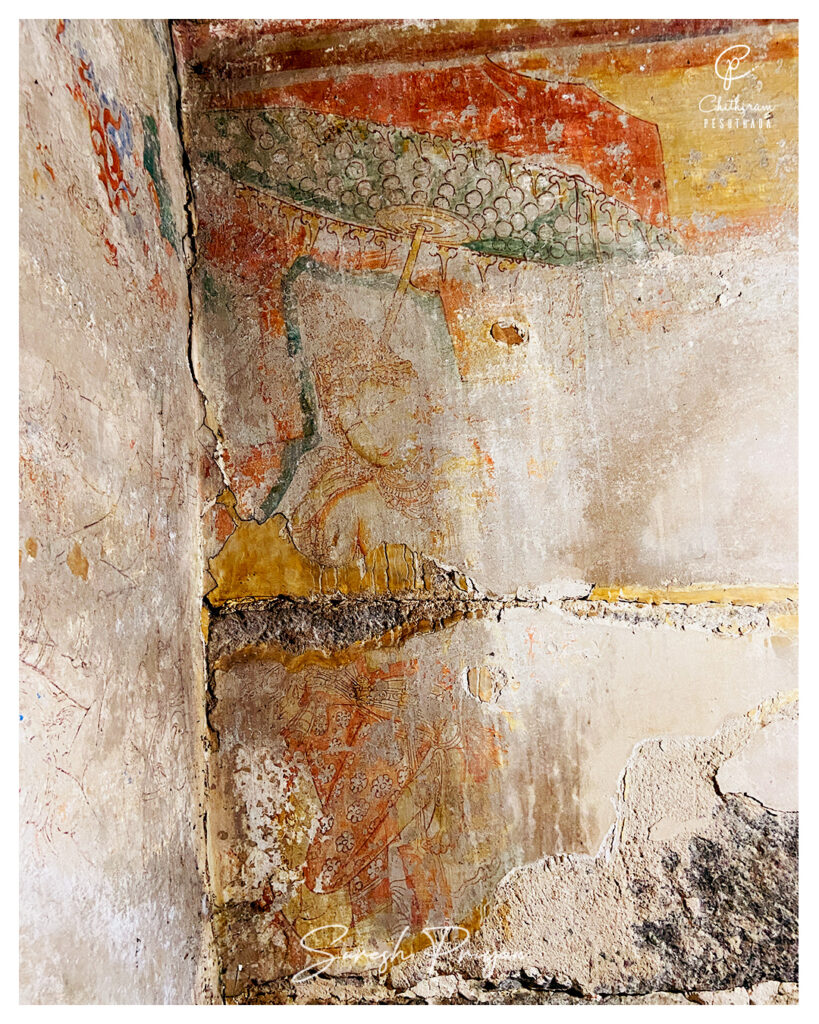

In the temple town of Kanchipuram—just 45 miles from Chennai—lie two remarkable treasures of South Indian art: the Kailasanatha and Vaikunthaperumal temples. These sacred spaces, built during the Pallava period (7th–8th centuries CE), were once adorned with vivid murals on their walls. Though many have faded over the centuries, what remains still offers a fascinating glimpse into the artistic mastery of the time.

In the 1930s, archaeologist and chemist S. Paramasivan from the Government Museum in Madras (Chennai) studied these ancient paintings in detail. His goal was to understand precisely how the Pallava artists created these murals—what materials they used, what techniques they followed, and how the paintings have withstood the test of time.

The Temples and Their Murals

- Kailasanatha Temple, built by King Narasimhavarman II (also known as Rajasimha), contains paintings on the inner walls of small shrines surrounding the main sanctum.

- Vaikunthaperumal Temple, built a few decades later by King Nandivarman II, has paintings located high up under the roof eaves and in small decorative niches on the tower (vimana).

Although many of these murals have sadly vanished, they are among the earliest examples of South Indian temple painting—older than those in Tanjore or Narthamalai. Some fragments were rediscovered in 1931 by the French archaeologist Jouveau Dubreuil.

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/c/chithirampesuthada

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/chithirampesuthadasuresh/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/chithirampesuthada/

Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/chithirampesuthada/

Web: https://chithirampesuthada.com/

How Were the Murals Made?

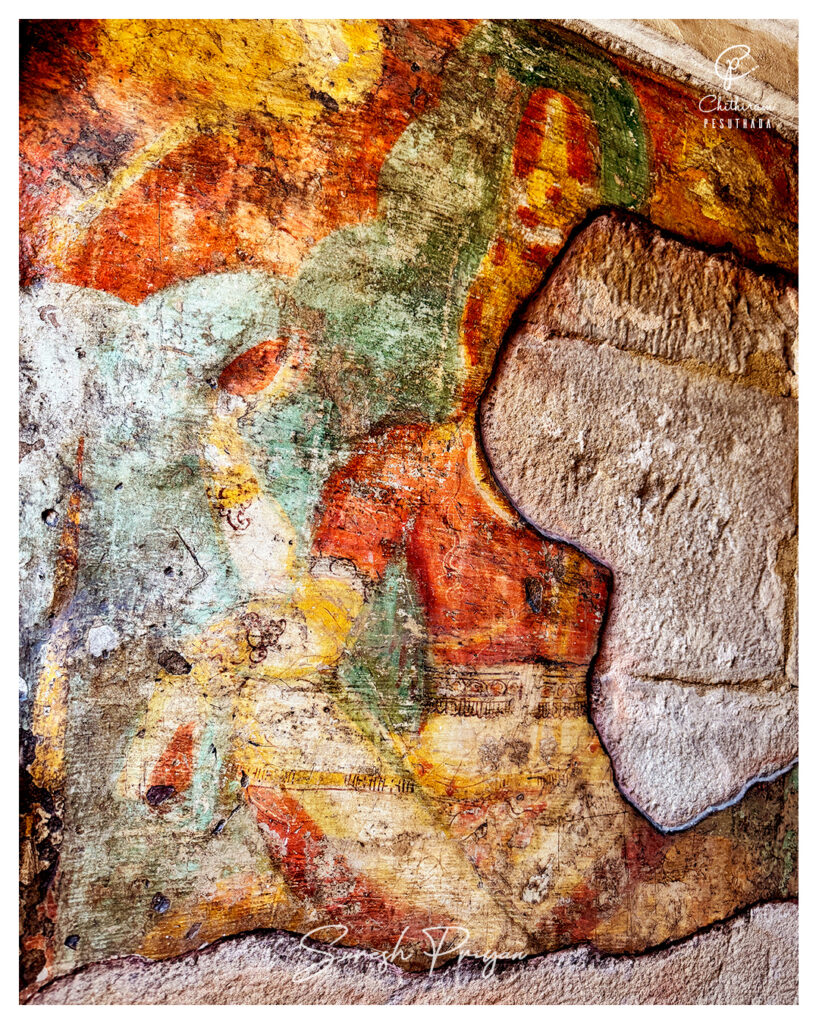

Paramasivan’s investigation revealed that the artists used a method similar to what’s called true fresco. This involves painting on a fresh, wet layer of lime plaster, allowing the pigments to bond with the wall as it dries, making the painting more durable.

Here’s what the wall had, layer by layer:

- A rough plaster base (called arriccio or rinzaffo), made of lime and sand.

- A smooth lime wash is applied over the base while still damp.

- Paint, made from natural pigments, brushed onto the surface before or after it dried.

Interestingly, in some parts of the Kailasanatha temple, there’s no rough plaster at all—just the lime wash applied directly onto the stone wall.

What Materials Did They Use?

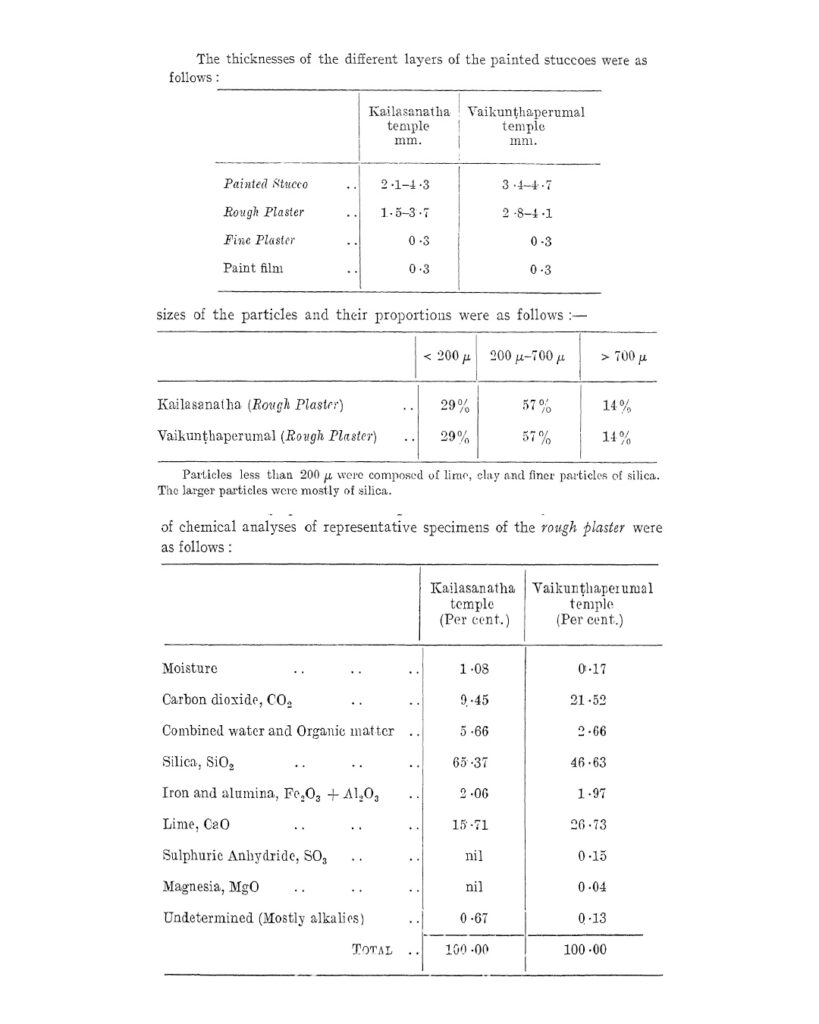

Chemical analysis of the plaster showed a mix of:

- Lime as the main binder

- Sand as filler

- Small amounts of iron, alumina, and carbonates

The artists used natural, earthy colours:

- Black from charcoal or carbon

- Red and yellow from ochres

- Green from a mineral called terre verte (green earth)

In some places, the pigments were mixed with lime and applied while the plaster was still wet (fresco), while in others, they were painted onto dry plaster (a method known as fresco-secco).

Why Does It Matter?

Understanding how these paintings were created helps conservators and archaeologists protect and preserve what remains. It also shows the level of sophistication achieved by Indian artists more than 1,200 years ago. They weren’t just skilled painters—they were also chemists in their own right, mastering materials and techniques to ensure their art could live for generations.

Thanks for supporting us!

To contribute:

PayPal us – paypal.me/sureshpriyan

Google Pay us – priyan.suresh@okicici